Stage plays have always provided material for the cinema, but recently there has been a series of productions going the other way (in fact, with The Fly, The Bitter Tears of Petra von Kant and Lost Highway amongst others, you could argue that the preferred ultimate destination is opera). And so the National Theatre is showing Peter Flannery’s adaptation 1994 Foreign Film Oscar-winner Burnt by the Sun, scripted by Rustam Ibragimbekov and director Nikita Mikhalkov.

SPOILER ALERT (throughout)

June, 1936. Colonel Sergei Kotov is at his dacha with his daughter Nadezhda (Nadia), his wife Marusia and her family. An old friend (and Marusia’s former lover) Mitya arrives unexpectedly. Some years previously, Kotov had ‘invited’ Mitya to join the NKVD (predecessors of the KGB) where, under cover of being an émigré musician, he betrayed several White officers. He has received orders to take Kotov to the Kremlin to be questioned about alleged spying. Mitya finds his duty coinciding with his desire for revenge.

Though it’s obviously a Chekhovian dacha-drama, the film occasionally breaks out into the countryside, but here, apart from the swimming trip (with the dacha in the backgound), it all takes place at home, which works surprisingly well.

The film achieved a remarkable success in working well for western audiences, while embedding dialogue, music and references that added additional layers for Russian viewers. In fact the English version was slightly cut to remove some of the more Russocentric elements, and Flannery has followed that, while making some additional cuts and introducing new things, notably a subplot involving the middle-aged maid Mokhova, a virgin who flirts with a passing van-driver.

Why a reference to Hamlet was replaced by Escalus I'm not sure: a nation of Bardophiles like Russia would be completely unfazed. One minor but definite improvement is cutting the film’s destructive burning orbs, though oddly there’s still a vestigial reference to them that could disappear without losing anything apart from a few seconds of stage time. The 'Holiday of the Stalinist Balloon-Makers’ subplot is also a bit troublesome. Though it leads to the film’s impressive climax and a dreadful moment for Mitya, it's hard to imagine how it could be staged: better simply cut it altogether, as the semi-symbolism here (looking and sounding like an off-stage asthmatic dragon) probably only confuses anyone who hasn’t seen the film.

There's also a clear missed opportunity: the film starts with Mitya receiving his orders and making a desultory attempt at Russian roulette to avoid the job. At the end he slits his wrists in his Moscow bath, ironically echoing the titular song’s line about crimson waters (in the sunset) and the suicide attempt that Marusia made when he left (enforcedly) without explanation. In the play Flannery cuts the opening scene and finishes with Mitya shooting himself at the dacha: surely including the prologue would have made a neat book-ending.

But the major change is to Kotov’s daughter, Nadezhda (Russian for ‘hope’). In the film she’s irreplaceably played by Mikhalkov’s own similarly-named six year-old daughter, but here she's about ten. Practicalities (including child-actor laws) probably forced the change but it’s sad to lose the innocence that is so overwhelming in the film: the dark end of the play’s first act makes Nadia aware of how the state is overwhelming private life, whereas in the film she remains cheeky and charming to the very end, making her fate all the more distressing.

But the major change is to Kotov’s daughter, Nadezhda (Russian for ‘hope’). In the film she’s irreplaceably played by Mikhalkov’s own similarly-named six year-old daughter, but here she's about ten. Practicalities (including child-actor laws) probably forced the change but it’s sad to lose the innocence that is so overwhelming in the film: the dark end of the play’s first act makes Nadia aware of how the state is overwhelming private life, whereas in the film she remains cheeky and charming to the very end, making her fate all the more distressing. Her role is also cut back in two of the film’s tent-pole scenes: her dialogue with Kotov on the boat is given to Marusia, though he still invokes the spirit of Chapayev and conveys his intense faith in the Soviet future. But more serious is the decision to restage Mitya’s crucial story-confession. In the film it's a long scene framed by a window in which he tells Nadia a ‘fairy story’, reversing and anagramaticising the family’s names to allude to his dark mission, while the rest of the family listen uncomfortably in the next room. The complex layering of audiences (Nadia; the family; and us) is simplified on stage and his motivation flattened as it he is less torn between a sense of duty and a desire to be challenged. Here it is lesss nuanced: Nadia sleeps on Kotov's breast while Mitya's story, a semi-overt confession, is to Marusia and the whole family.

Her role is also cut back in two of the film’s tent-pole scenes: her dialogue with Kotov on the boat is given to Marusia, though he still invokes the spirit of Chapayev and conveys his intense faith in the Soviet future. But more serious is the decision to restage Mitya’s crucial story-confession. In the film it's a long scene framed by a window in which he tells Nadia a ‘fairy story’, reversing and anagramaticising the family’s names to allude to his dark mission, while the rest of the family listen uncomfortably in the next room. The complex layering of audiences (Nadia; the family; and us) is simplified on stage and his motivation flattened as it he is less torn between a sense of duty and a desire to be challenged. Here it is lesss nuanced: Nadia sleeps on Kotov's breast while Mitya's story, a semi-overt confession, is to Marusia and the whole family.One of the film’s most evocative elements is the music, though there’s relatively little by Mikhalkov’s regular composer Eduard Artemyev. It’s more of a patchwork of popular songs from the 1930s including the almost-titular tango (the film changes it from The Weary Sun to Wearied by the Sun), which runs throughout the film as a bittersweet refrain. Originally Polish, its lyric about parting lovers meant it acquired the nickname “suicide tango”, another dramatic irony. Later, it was adapted and made a hit by Soviet jazz luminaries including Leonid Utyosov and Alexander Tsfasman. It also became enough of a symbol to pop up in Norshtein’s Tale of Tales, Kieslowski’s Three Colours: White and even (in its Polish form) Schindler’s List. I could have done with hearing it a few more times, as you do in the film.

This is the original (not, I think, the performance that's in the film).

And this is what Artyemev does with it for the trailer

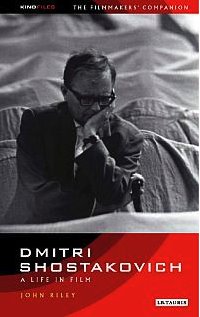

Wisely they’ve kept the disturbingly manic performance of Offenbach’s Can-can, also used by Shostakovich as a symbol of a corrupt regime in New Babylon. In fact Shostakovich pops up a couple more times: on the way to the Kremlin Kotov breaks into a tune that any Russian would recognise: The Song of the Counterplan, indissolubly linked to the 1930s and a tune to which Shostakovich returned more than once, as explained in this book. At the National, Kotov simply suggests singing some folk songs (a few bars wouldn’t have come amiss, though they’d have to pay Booseys!) And there’s a brief reference to the ever-popular Aviators' March ("We Were Born to Make Fairy Tales Come True"). Finally, I wonder if the film's fragment of Shostakovich’s Fourteenth String Quartet is a little Artemyevan joke: the quartet was dedicated to the cellist Sergei Shirinsky: Kotov’s first name is, of course, Sergei. But the staging dispenses with much of the music, making the texture a bit thinner.

Burnt by the Sun is an intensely patriotic piece: Mikhalkov-Kotov saves “the people’s wheat” and fights for the Motherland and defends the future he envisages for it. Whatever Bolshevism later became, he cleaves to its initial stated aims and the play, if anything, strengthens that, with Kotov more forcefully reminding us of his peasant beginnings and the cowardice of the bourgeoisie who ran before him rather than defending their beloved lifestyle. That also slightly changes the dynamic with the rest of the family as he more openly despises them for that.

But none of these changes reduce the power of the piece and, as I said, Flannery has made it work brilliantly for a Western audience.

Meanwhile, Mikhalkov is currently producing Burnt by the Sun 2, a blockbuster two-part epic. Part one is set to open on 9 May 2010, the 65th anniversary of Victory Day, and the film will then be expanded as a 12-part mini-series.

For this he has reanimated Kotov, Marusia and Mitya who all died or were reported dead in the first film! Mikhalkov's father Sergei, of course wrote t

he lyrics of the Soviet national anthem and reworked them for a new audience when Putin revived it, and Nikita’s actions sometimes bring him to the edge of being an apologist for a cult of personality. Hence a visit to the set from Vladimir Putin, with his newly imposed official view of Stalinism, might raise an eyebrow but the director assures us the film will denounce the tyrant.

he lyrics of the Soviet national anthem and reworked them for a new audience when Putin revived it, and Nikita’s actions sometimes bring him to the edge of being an apologist for a cult of personality. Hence a visit to the set from Vladimir Putin, with his newly imposed official view of Stalinism, might raise an eyebrow but the director assures us the film will denounce the tyrant. Finally, a small plug for Birgit Beumers' excellent guide to the film, published by Tauris.

Finally, a small plug for Birgit Beumers' excellent guide to the film, published by Tauris.